It sounds like an unlikely claim; smartphone making you better with a professional camera system, but for me, it is exactly what happened, and the journey that brought me there started in the strangest of circumstances: a global pandemic, an empty coastline, and a camera bag I eventually stopped reaching for.

When Lockdown Pushed Me Towards the Coast

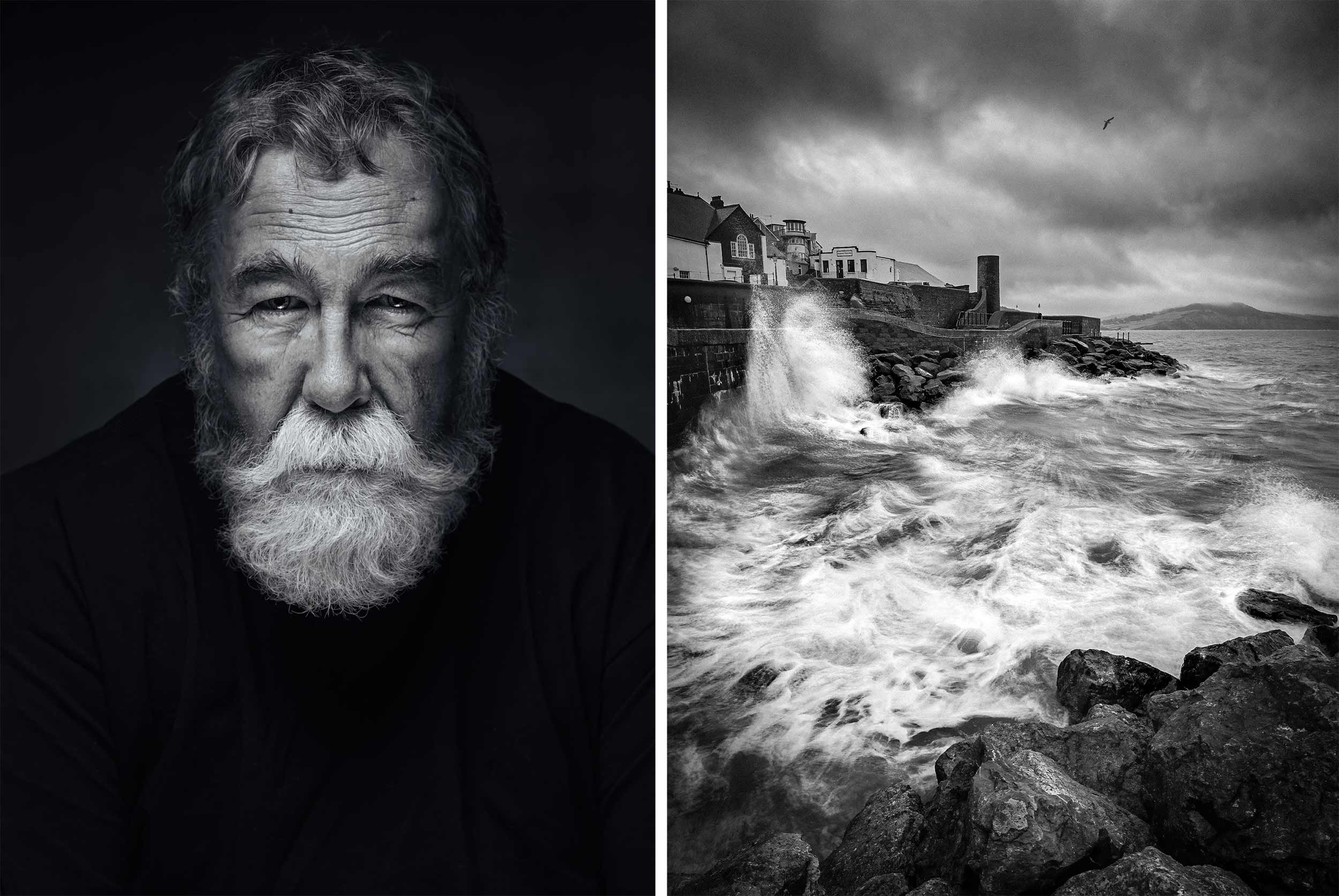

Portrait photography is what I do, it’s the heart of my work, but in the early days of the COVID pandemic, with people unable to gather, I needed an outlet. I needed to get out and stay creative. Fortunately, the nature of my work meant I had the permission to do so, even when so many others could not.

So I turned to landscapes, and more specifically, seascapes. I headed to the coast with my Sony A7R IV, invested in filters and all manner of specialist kit, and prepared to throw myself into a new discipline. What I found instead though, was that I had thrown myself into a wall.

The Problem with Too Much Kit

The gear was overwhelming. I was new to landscape photography, new to reading the light in that environment, and new to the entire creative process involved.

Instead of being absorbed by the scene in front of me, I was absorbed by the technical decisions.

Which filter? What exposure? How do I handle this brightness range?

The equipment that was supposed to help me create better images was, in practice, creating a barrier between me and actually photographing the scene.

Out of frustration more than strategy, I started leaving the heavy camera bag in the car when I first arrived at a location. I would take my iPhone and simply walk, scout, and look for compositions before going back to collect the proper gear.

But, what was meant to be a workaround, turned into a revelation.

When the iPhone Stopped Being a Scouting Tool

The images I was capturing purely for composition reference were genuinely looking good; not just useful as guides, but good in their own right.

That realisation shifted everything. Suddenly, the iPhone was not just a note-taking device; it had become a creative challenge: could I get a shot with my mirrorless that was meaningfully better than what I had already captured on my phone?

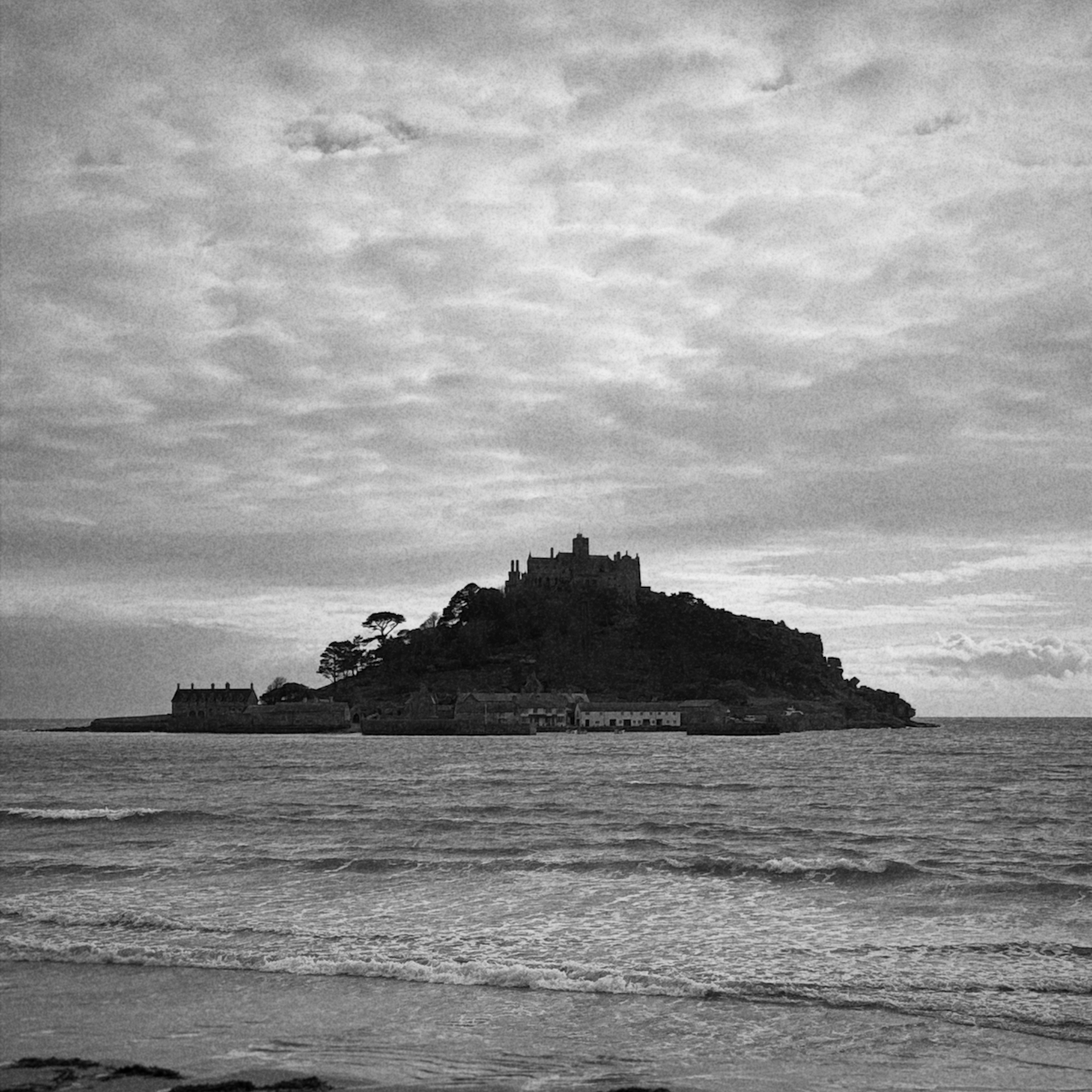

That question drove me forward, and over the years that followed, I found myself thoroughly absorbed in seascape photography, increasingly using the iPhone as my primary tool at the coast. My portrait work never wavered, that always remained with my mirrorless system, but for the seascapes, the iPhone became its own discipline.

Reexpose and the Long Exposure Workflow

A big part of what made this work was discovering the Reexpose app. Long exposure photography, the kind that smooths water into silk and turns crashing waves into mist, had always required filters, tripods, and careful technical management with my mirrorless. With Reexpose on the iPhone, I could achieve genuinely compelling long exposures without any of that overhead.

This is the nature of computational photography. The iPhone handles so much of what would otherwise require deliberate technical decisions, and for a long time, I thought that was the whole story. Remove the friction, get the shot, enjoy the process.

But what I came to understand was that the phone was doing something far more valuable than saving me time.

What the iPhone Was Actually Teaching Me

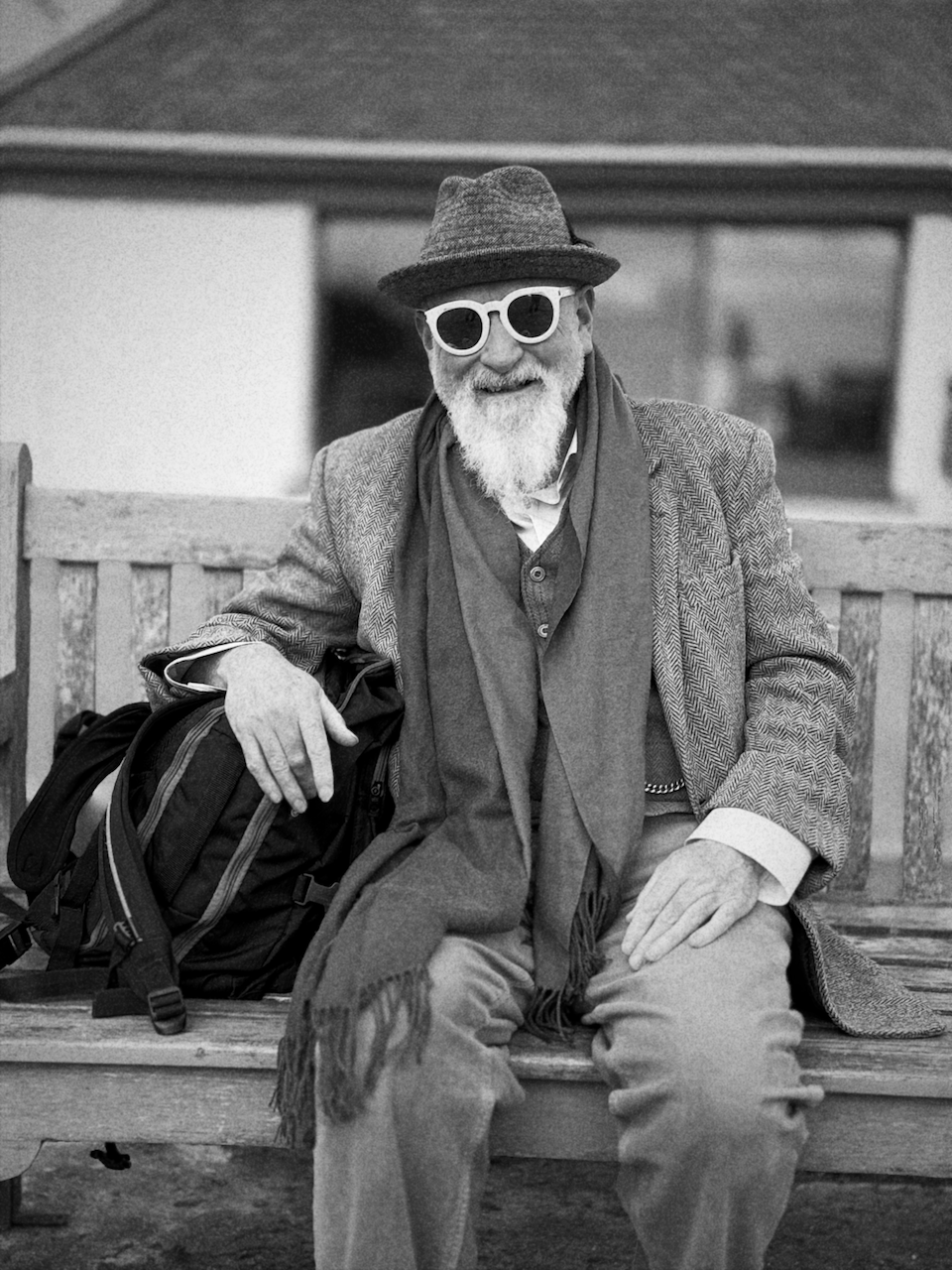

Without the weight of technical decisions pulling at my attention, I began to truly absorb my surroundings. The sights, the smells, the sounds, the feeling of being somewhere specific at a specific moment. I was learning to read light not as a technical problem to solve but as something to feel and respond to. I was developing an instinct for composition that no amount of deliberate study had given me.

The iPhone removed the friction that had always sat between me and pure creative engagement, and in doing so, it allowed me to build a visual language and a sensitivity to light that I was then able to bring back to my mirrorless work.

The technical side of things, the things I had found so overwhelming at the start, began to feel natural; not because I had studied harder, but because I had spent years simply being present with the subject, free from distraction. The craft followed the instinct, rather than fighting against it.

The Lesson for Any Photographer

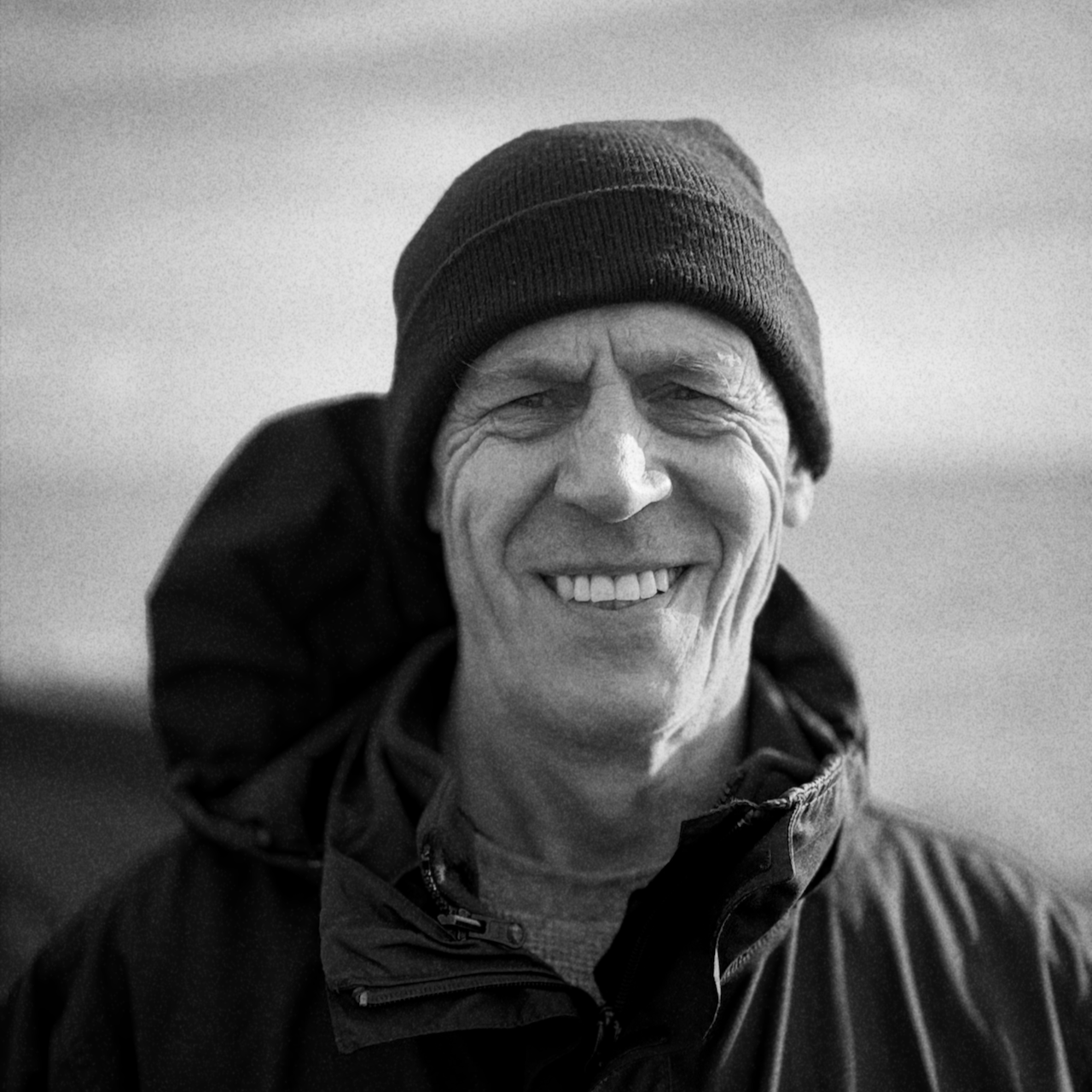

Don’t get me wrong here … I’m not suggesting everyone should put down their camera and reach for their phone. What I am suggesting however, is that whatever removes the barrier between you and creative immersion is worth taking seriously, regardless of how unconventional it looks.

For me, it happened to be seascapes with an iPhone during a pandemic. For you, it might be something else entirely. But the principle holds. When you can stop thinking about the tool and start thinking about the image, something shifts, and that shift stays with you, long after you pick the bigger camera back up.

The iPhone did not replace my mirrorless photography, it made it better, and I suspect it will keep doing so for a long time yet.